Spotting the Culprit: What Do Ticks and Their Bites Really Look Like?

Why Identifying Ticks Quickly Matters for Your Health

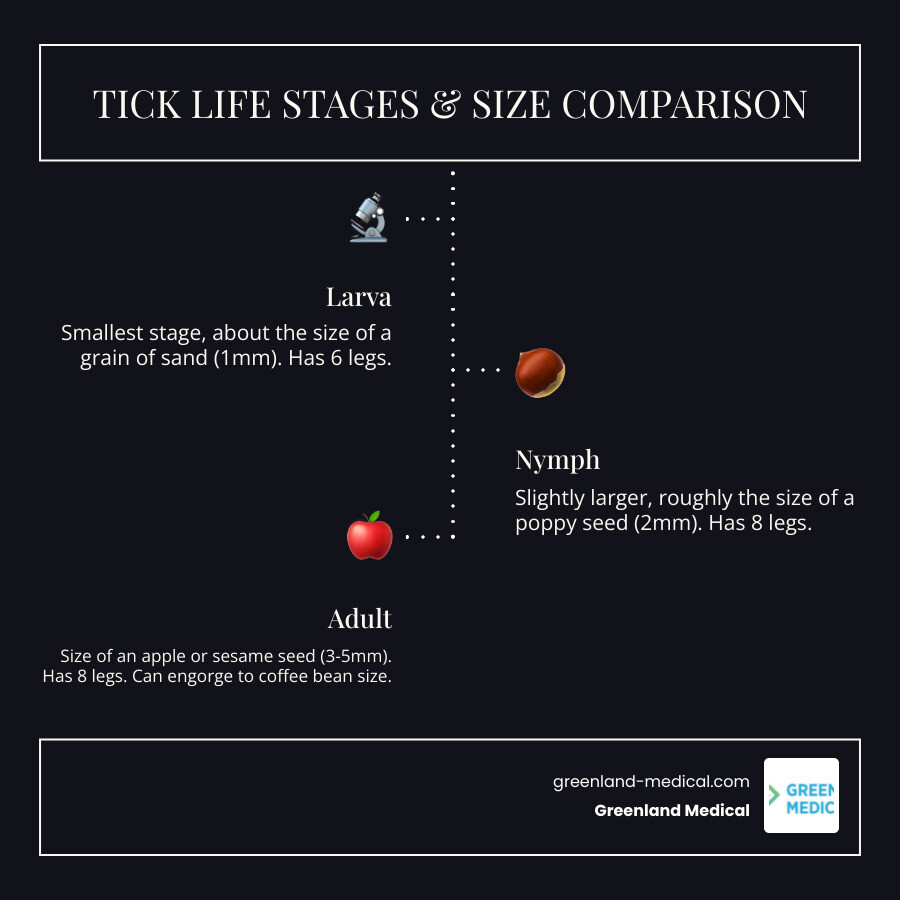

What does a tick look like? Ticks are small, oval-shaped arachnids with flat bodies and no wings. Their colour varies from reddish-brown to black or greyish-white. Larvae have 6 legs and are as small as a grain of sand. Nymphs and adults have 8 legs; nymphs are the size of a poppy seed, and adults are about the size of an apple seed. When engorged with blood, ticks swell dramatically, becoming round, greyish, and as large as a coffee bean.

Quick Identification Guide:

Size: Larvae (grain of sand) → Nymphs (poppy seed) → Adults (apple seed)

Legs: 6 legs (larvae) or 8 legs (nymphs and adults)

Shape: Flat and oval when unfed; round and swollen when engorged

Color: Reddish-brown, dark brown, black, or greyish-white

Features: No wings, visible mouthparts

Finding a tick is unsettling because they can transmit bacteria and viruses that cause serious diseases like Lyme disease. Identifying them is challenging due to their tiny size and changing appearance throughout their life cycle.

Understanding what ticks look like at each stage is crucial for quick spotting, safe removal, and assessing your risk. For those dealing with chronic fatigue or unexplained symptoms after spending time outdoors, knowing if you've been exposed to ticks can be a vital clue.

I'm Dr Andrew Greenland, and in my functional medicine practice, I help patients investigate the root causes of chronic illness, including tick-borne infections that conventional testing may miss. Recognising what does a tick look like is the first step in addressing these complex health challenges.

What Does a Tick Look Like? A Detailed Breakdown

To understand what does a tick look like, it's helpful to know they aren't insects. They are arachnids, related to spiders and mites. This explains some of their key features.

Ticks are small, oval-shaped, and have flat bodies when unfed. They can't fly or jump, waiting instead on vegetation for a host to pass by. Their colours vary from reddish-brown and dark brown to black or greyish-white. Before feeding, most are just 1-3mm long. After a blood meal, they can swell to the size of a coffee bean (over 1cm).

Tick identification is challenging due to their small size, change after feeding, and the number of different species. However, knowing the type of tick can help doctors assess your risk for specific diseases.

Basic Tick Anatomy

A tick's body segments are fused, giving it a single, unified appearance. The easiest way to identify a tick's life stage is by counting its legs. Larvae have six legs, while nymphs and adults have eight legs.

The mouthparts (capitulum) have barbs that anchor the tick into the skin and a tube for drawing blood. When attached, these mouthparts are buried, so you may only see the tick's body. This is why they are difficult to remove.

The scutum is a hard, shield-like plate on a tick's back, crucial for identifying different types. Hard ticks have a prominent scutum, while soft ticks do not.

Hard Ticks vs. Soft Ticks

Ticks fall into two main families: Ixodidae (hard ticks) and Argasidae (soft ticks).

Hard ticks are the type most people in the UK encounter. They are defined by the hard scutum on their back. In males, this shield covers their entire back; in females, it covers only a portion, allowing their bodies to expand when they feed. Their mouthparts are visible from above. Hard ticks have an oval or teardrop shape and stay attached for several days. The sheep tick (Ixodes ricinus), the most common tick in the UK and the primary carrier of Lyme disease, is a hard tick.

Soft ticks are less common in the UK for human bites. They lack a hard scutum, giving their bodies a leathery, wrinkled texture. Their mouthparts are hidden underneath their body. Soft ticks are rounder and feed for shorter periods (minutes to an hour). They prefer to live in the nests and burrows of their hosts, such as birds and bats, so you are less likely to encounter one.

Here's a quick comparison:

Feature Hard Ticks (Ixodidae) Soft Ticks (Argasidae) Body Shape Oval, teardrop, or pear-shaped; flat when unfed More rounded or oblong; leathery, wrinkled appearance Scutum Present (hard shield) Absent Mouthparts Visible from above Not visible from above (located underneath) Feeding Time Days (e.g., 24 hours to several days) Hours (e.g., minutes to a few hours) Engorgement Body swells significantly, scutum remains fixed Body swells moderately and uniformly Appearance Resembles a tiny spider or seed More like a small, wrinkled bean or pebble Commonality More frequently encountered by humans and pets Less frequently encountered by humans

A Tick's Change: From Larva to Adult

Ticks don't just grow bigger; they transform through distinct stages, each looking quite different. Understanding this life cycle is helpful when you're trying to determine if that tiny speck on your skin is a threat.

Ticks have four life stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. At every stage after hatching, they need a blood meal to survive and mature. This means a tick of any size could pose a risk.

The four life stages of a hard tick, like the sheep tick.

What does a tick look like at different life stages?

A tick's appearance changes dramatically as it grows, which can make identification tricky.

Larvae are the tiniest stage, often called "seed ticks." They are barely visible, about the size of a grain of sand, and have only six legs. Their colour is pale and almost translucent. Because they are so small, most people never notice them, yet they can still transmit disease.

Nymphs are the next stage. After feeding, larvae moult into nymphs, which are about the size of a poppy seed and now have eight legs. The nymph stage is when most people get bitten without realising it. They are small enough to go unnoticed and are active during warmer months. Their colour ranges from translucent to light brown, blending in easily with skin.

Adult ticks are finally large enough to be spotted more easily. An unfed adult is about the size of an apple seed and has eight legs. Their bodies are more robust and their colouring more distinct—typically reddish-brown or dark brown. Adult females are of particular concern because they can lay thousands of eggs after feeding. The good news is that adults are easier to see and remove before they have been attached long enough to transmit disease.

The progression from a six-legged larva to an eight-legged nymph and adult is a reliable way to identify the stage. For visual guides, resources like Lyme Disease Action can help you see these differences.

Male vs. Female Ticks

In adult hard ticks, telling males and females apart is relevant because their feeding behaviours differ.

Male ticks are generally smaller and flatter than females. Their hard scutum (the shield on their back) covers nearly their entire body, which prevents them from expanding much when they feed. They take smaller blood meals and remain relatively flat.

Female ticks are built for expansion. Their scutum only covers the front portion of their back, allowing the rest of their body to swell dramatically as they feed. They need a large blood meal to produce eggs. When you find a tick that is swollen like a grape or coffee bean, it is almost certainly an engorged female that has been feeding for some time. An engorged tick indicates a longer attachment time, which increases the risk of disease transmission.

A Guide to Common UK Tick Species

Knowing what does a tick look like in your area is key, as different species carry different diseases. In the UK, one species is responsible for the vast majority of tick bites on humans.

Different tick species, such as those shown here, have distinct appearances. In the UK, the sheep tick is most common.

Sheep Tick (Ixodes ricinus)

The sheep tick, also known as the castor bean tick, is the most common tick in the UK and the primary carrier of Lyme disease. It is widespread across the country, found in woodlands, grasslands, moorland, and even urban parks and gardens. If you are walking in areas with long grass, bracken, or leaf litter, you are in their territory.

So, what does a tick look like when it's a sheep tick? They are very small. An unfed adult female is about the size of a sesame seed (3-4mm long). Nymphs are even smaller, around the size of a poppy seed (1-2mm), which is why they often go unnoticed.

The adult female has a distinctive two-tone appearance. Her body is reddish-brown, with a dark brown or black scutum (shield) covering the front part of her back. Her legs are also dark. Adult males are smaller and uniformly dark brown or black.

When fully engorged, a female sheep tick swells to the size of a small grape or coffee bean (up to 1cm). Her body becomes rounded and greyish, making the original colouring less obvious.

These ticks are most active from spring to autumn but can be found at any time of year when the temperature is above freezing. While they are the main vector for Lyme disease, they can also transmit other, much rarer, infections like Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE) in specific parts of the UK and Europe.

Other UK Ticks

While Ixodes ricinus is the main concern for humans, other tick species exist in the UK, such as the hedgehog tick (Ixodes hexagonus). This species is often found in gardens and urban areas and may occasionally bite humans or pets.

For anyone wanting to learn more about tick identification and risks in the UK, the government's Ticks and your health information leaflet is an excellent resource.

After the Bite: Identifying Engorged Ticks and Bite Marks

Finding an attached tick can be unsettling. Understanding what does a tick look like when feeding, and what a bite looks like afterward, helps you respond correctly. Ticks attach firmly with their mouthparts and can remain feeding for several days.

During this time, their saliva, which contains an anaesthetic so you don't feel the bite, can transmit pathogens. The longer an infected tick is attached, the greater the risk of disease transmission. For Lyme disease, the tick generally needs to be attached for over 24 hours to transmit the infection.

Comparing an unfed tick (left) to a fully engorged tick (right).

What does a tick look like when engorged?

The change a tick undergoes while feeding is dramatic. An unfed tick is flat and oval, but once engorged with blood, its appearance transforms, especially in females.

The body swells considerably. What was flat becomes round and bulbous, growing to the size of a coffee bean or small grape.

The colour shifts. The tick's colour often changes from dark brown or black to a greyish-white or light grey.

The head appears buried. The swollen body makes the mouthparts seem to disappear into the skin. The hard scutum on a female remains visible near the head, but the rest of her body is vastly expanded.

Recognising an engorged tick is a sign it has been feeding for some time. Prompt and proper removal is essential. Use fine-tipped tweezers to grasp the tick as close to the skin as possible and pull upward with steady, even pressure. Do not twist or crush the tick. After removal, clean the bite area with an antiseptic wipe or soap and water. The NHS offers clear advice on removing ticks.

Identifying a Tick Bite

A tick bite is usually painless and may go unnoticed. After the tick is removed, certain signs can indicate a bite and whether you should be concerned.

Initially, you might see a small red bump, similar to a mosquito bite. The area may be slightly itchy or swollen. For many, this is the only reaction.

Watch for the bull's-eye rash. The most well-known sign of Lyme disease is the "bull's-eye" rash, known as erythema migrans. It typically appears 3 to 30 days after the bite and gradually expands. It often has a red outer ring with a clearer centre, but it can also be uniformly red or have an unusual shape. Crucially, not everyone with Lyme disease gets the rash—estimates suggest up to 30% of people do not.

Pay attention to flu-like symptoms. A tick bite can trigger symptoms like fever, chills, headaches, muscle aches, joint pain, and fatigue, even without a rash. Because these symptoms are general, they can be mistaken for other illnesses, which is why noting a tick bite is so important.

If you experience a rash or any of these symptoms after a tick bite, seek medical advice promptly. Early diagnosis and treatment are key to preventing long-term complications. To understand the range of symptoms, you can learn more about Lyme disease symptoms from the NHS. For those with chronic symptoms, exploring tick-borne infections as a potential root cause can be an important step. Learn more about Lyme disease symptoms and our approach to Lyme disease treatment at Greenland Medical.

Frequently Asked Questions about Tick Identification

Tick identification can be confusing. Here are answers to some of the most common questions I hear from patients.

How can you tell a tick from a bed bug or other small insect?

Understanding what does a tick look like compared to other pests can help you identify it correctly.

Count the legs: Adult and nymph ticks are arachnids and have eight legs. Bed bugs are insects and always have six legs. (Tick larvae also have six legs but are minuscule).

Check the body shape: Ticks have a single, fused body that appears oval. Bed bugs have visibly segmented bodies with a separate head, thorax, and abdomen.

Observe their behaviour: Ticks embed their mouthparts and feed for days. Bed bugs feed for a few minutes and then hide, often leaving bites in a line or cluster.

How long does a tick stay attached?

Unlike a mosquito, a tick can stay attached and feed for several days.

The exact duration depends on the tick's life stage. Larvae may feed for up to 3 days, while nymphs can stay attached for 3-5 days. Adult female ticks are the longest feeders, remaining attached for a week or more to get enough blood to lay their eggs.

Fortunately, many tick-borne pathogens, including the bacteria that causes Lyme disease, require at least 24-48 hours of attachment time to be transmitted. This is why daily tick checks after being outdoors and prompt removal are so effective at preventing illness.

Do all ticks carry diseases?

No, not all ticks carry diseases, and not every tick bite will make you sick. However, it's impossible to know if a specific tick is infected just by looking at it.

The risk varies by species and location. In the UK, the sheep tick (Ixodes ricinus) is the main species of concern and is known for carrying the bacteria that causes Lyme disease. Infection rates in ticks vary across the country, with higher-risk areas including the Scottish Highlands, the Lake District, New Forest, and other rural and woodland areas. However, infected ticks can be found in urban parks and gardens, too.

Because you can't tell if a tick is infected, prompt removal is your best defence. Removing a tick within 24 hours significantly reduces your risk of infection, as the pathogens need time to travel from the tick's gut into your bloodstream.

If you've been bitten, don't panic. Monitor the bite site for a rash and watch for any flu-like symptoms in the following weeks. If you have any concerns, contact a healthcare provider.

Taking the Next Step After a Tick Bite

Knowing what does a tick look like is a powerful first step in protecting your health. It allows you to spot them early, remove them safely, and monitor for warning signs. However, tick-borne illnesses don't always present with a clear bull's-eye rash. Symptoms can be subtle and vague—chronic fatigue, brain fog, or persistent pain—and may trace back to a bite you never noticed.

At Greenland Medical, we see many patients struggling with unexplained health challenges. We understand that chronic illness often has deep roots, and sometimes those roots lead back to infections that conventional medicine overlooks. Our functional medicine approach means we dig deeper to find and address the underlying causes.

We look at your whole story—your symptoms, history, and biochemistry—to create a personalised plan. If you're dealing with chronic symptoms and wonder if a tick bite could be part of the picture, we're here to help you find answers.

For those concerned about Lyme disease or other tick-borne illnesses, we offer comprehensive testing and treatment strategies designed to uncover hidden infections and restore your health.

Learn more about our approach to Lyme Disease Treatment

We invite you to explore how our integrative approach can help you get to the root of your health issues through Functional Medicine, Naturopathy Services, and Integrative Medicine. You don't have to steer these challenges alone.